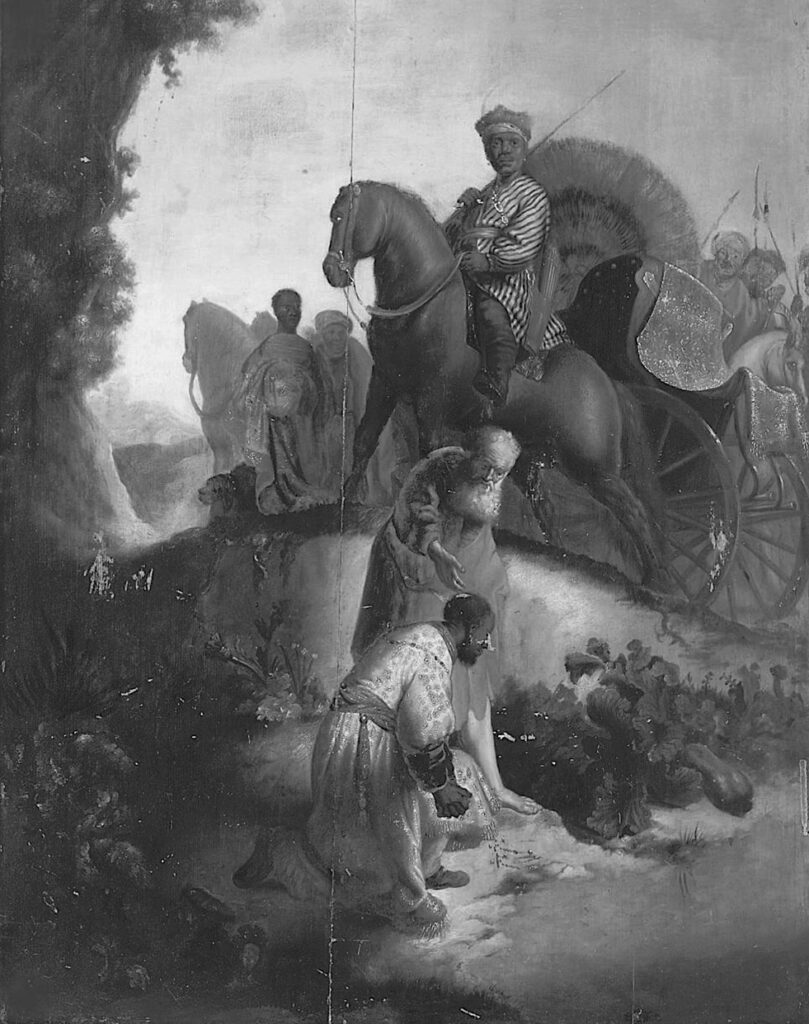

The rediscovery of a lost painting

by Rembrandt van Rijn

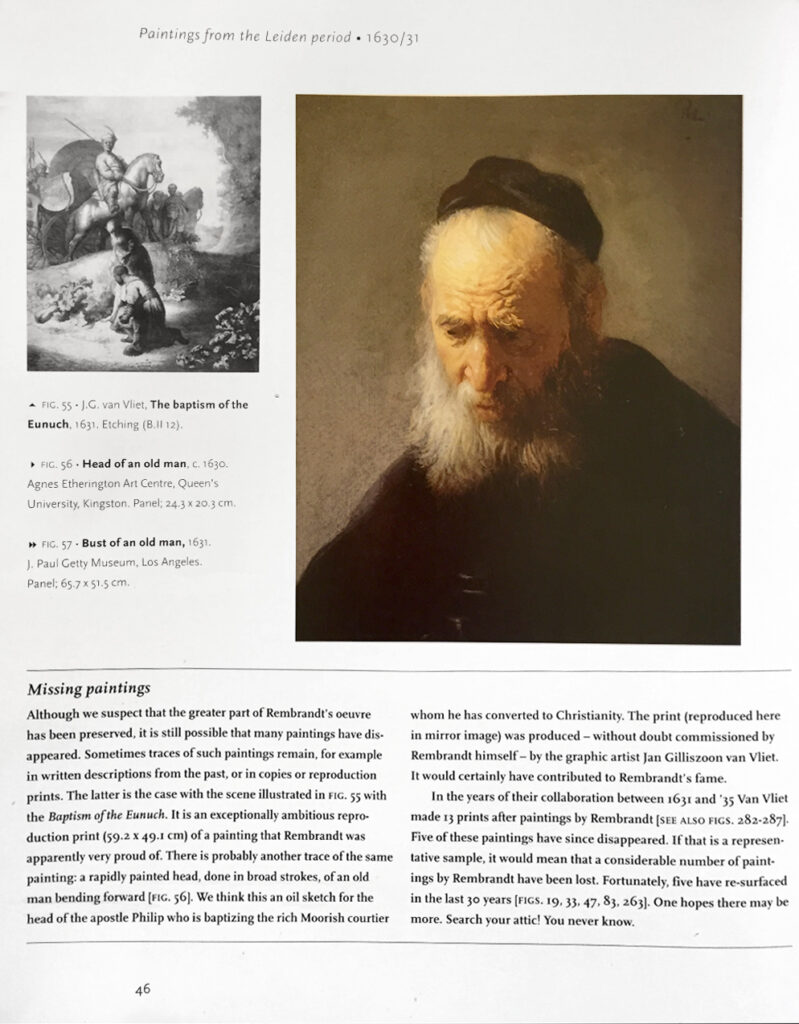

“The Baptism of the Eunuch, ca. 1630 […] a painting that Rembrandt was apparently very proud of.”

Ernst van de Wetering, A Life in 180 Paintings, Missing paintings p. 46, Local World BV, 2008.

Artwork Details

Title: The Baptism of the Eunuch

Artist: Rembrandt van Rijn

Date: circa 1630

Medium: oil on oak panel

Dimensions: 64,8 x 95,3 cm

Signature, Inscriptions: signed with an incomplete date

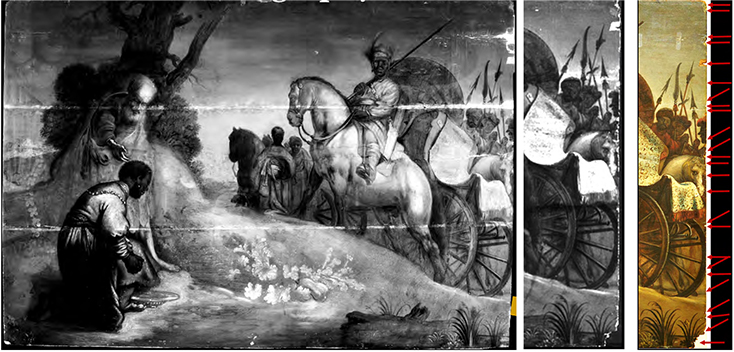

See the painting in its present state

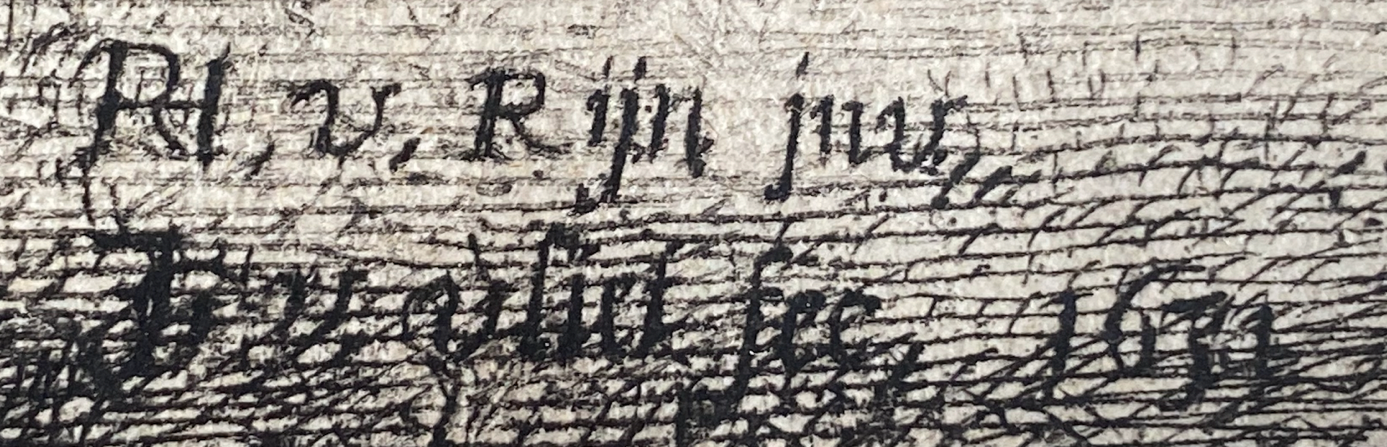

The biblical passage from the New Testament (Acts 8:28-39) recounts the encounter between the apostle Philip and an Ethiopian eunuch. Beneath the ancient ruins of Jerusalem, St. Philip, a renowned exegete, sits writing, his silhouette etched against the crumbling city. A figure appears—an angel sent by the Lord, with folded wings—bidding him to leave his books and seek the Ethiopian eunuch, the envoy of the queen of Candace, who is lost in the mysteries of the Book of Isaiah. St. Philip explains the passage (Isaiah 53:7-8) that the eunuch struggles to understand. Moved by faith, the eunuch requests to be baptized. Together, they cross bridges and winding paths, arriving at a serene riverbank where an extraordinary baptismal scene unfolds.

Attributions

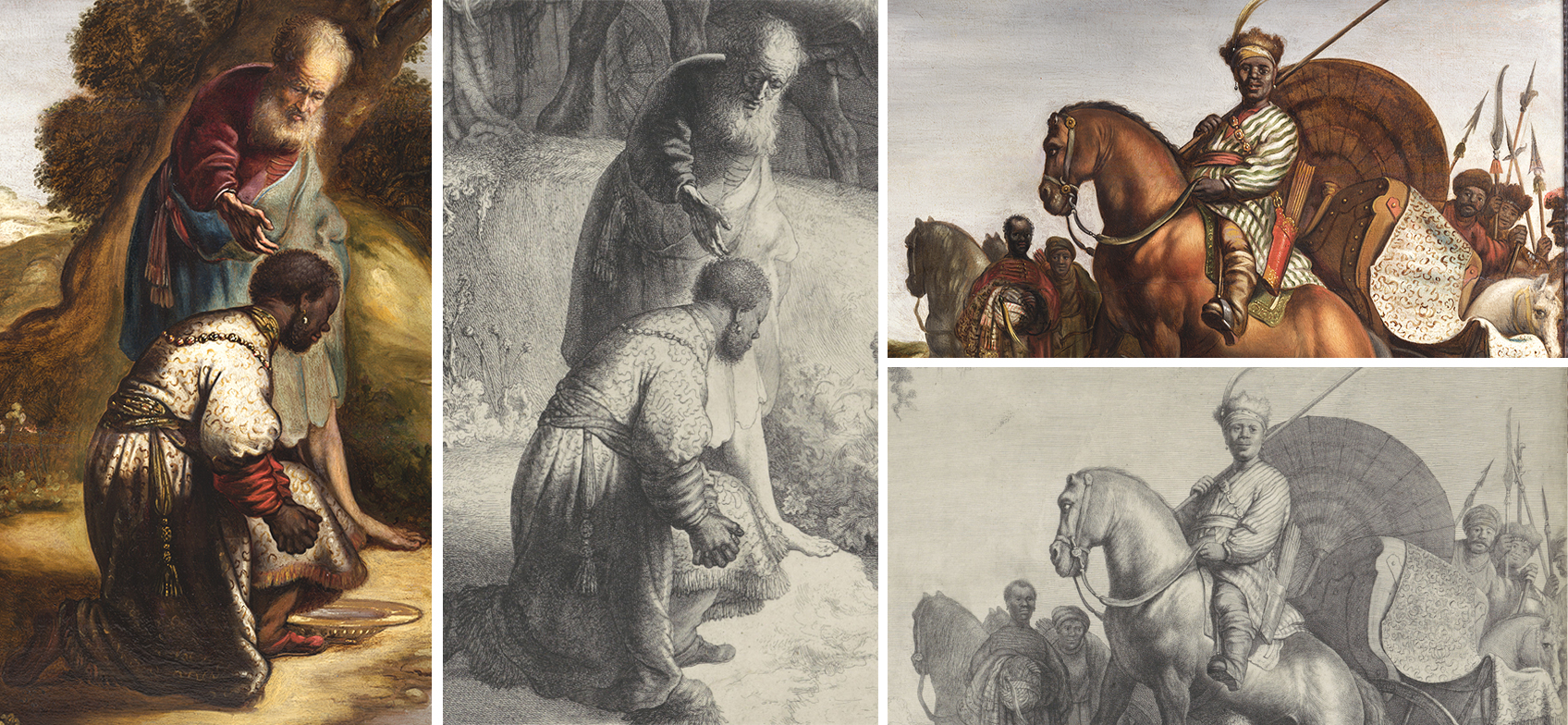

Before its recent rediscovery, this compelling biblical landscape was documented in a preparatory drawing by Rembrandt (c. 1630), used by J. G. van Vliet for a reproduction print in 1631, and was acquired directly from Rembrandt and reproduced by Claude Vignon in 1641. It later resurfaced at auctions in Amsterdam (1695) and Christie’s London (1798, 1973), catalogued as Rembrandt, before falling into obscurity. Its reattribution process began in 2019, provisionally proposed as a work by Rembrandt and his studio by Gary Schwartz and Christian Vogelaar. Since 2023, based on comprehensive documentary evidence, stylistic evaluation, and scientific analysis, the work has been attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn himself by Gary Schwartz, Prof. Dr Volker Manuth, and Ger Luijten and substantiated by Ernst van de Wetering’s authoritative writings.

(As is frequently the case with works from Rembrandt’s later Leiden period onward, the possibility of minor workshop participation cannot be totally excluded.)

The Baptism of the Eunuch by Rembrandt, ca. 1630, is exceptionally well-documented compared to many other paintings of his œuvre.

How did key insights provided by Ernst van de Wetering lead to the rediscovery of a lost painting?

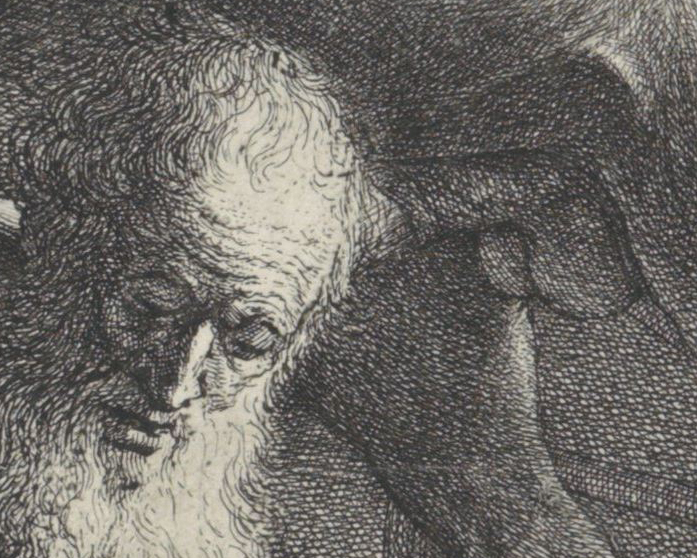

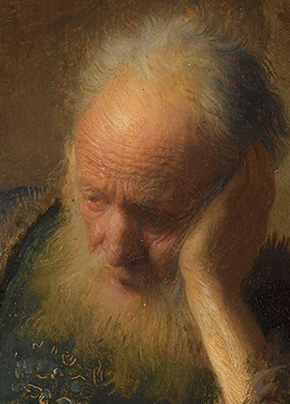

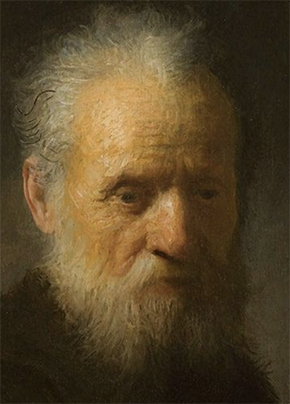

Ernst van de Wetering outlines the criteria for rediscovering Rembrandt’s lost Baptism of the Eunuch (1630), emphasizing its direct relationship and resemblance to The Head of the Old Man in a Cap alongside Saint Philip, as well as motifs reproduced in J.G. van Vliet’s engraving: “Sometimes traces of such paintings remain, for example in written descriptions from the past, or in copies or reproduction prints” […] “There is probably another trace of the same painting: a rapidly painted head, done in broad strokes, of an old man bending forward. […] an oil sketch for the head of the apostle Philip who is baptizing the rich Moorish courtier whom he was converted to Christianity.” (A Life in 180 Paintings, p. 46, “Missing paintings”, Local World BV, 2008).

Head of an Old Man in a Cap (c. 1630) and the head of Saint Philip in the present painting exhibit the same painterly touch, further reproduced by Van Vliet’s faithful etched detail.

According to van de Wetering, in Corpus IV, The Self-Portraits, Dordrecht, Springer, 2005, p. 628: “It is most likely that the present painting (The Head of the Old Man in a Cap) served as an oil sketch with an eye to the (now lost) Baptism of the Eunuch, a print of which was made in 1631, also by van Vliet.” At the time the Baptism of the Eunuch, ca. 1630 was thought to be lost; it only reappeared in 2019.

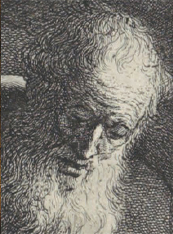

For the first time, Rembrandt chose the engraver J. G. van Vliet to execute a printed reproduction of one of his favourite compositions, The Baptism of the Eunuch, as confirmed by the inscription at the bottom of the plate.

“Van Vliet’s indication on the print after Oil study of an old man in a cap, c. 1630, that Rembrandt was the ‘inventor’ of the image concerned, should in my view be accepted as sound evidence that this painting (and the other paintings copied by Van Vliet) must have been from Rembrandt’s hand.” E. v. d. Wetering, Corpus VI , Chapter I, What is a Rembrandt ? A personal account, p. 41

Print copies after Rembrandt

There are two contemporaneous print copies of the painting in different formats, both bearing the inscription “Rembrandt invent”: J.G. van Vliet’s engraving from 1631 and C. J. Visscher’s engraving from 1631-1641.

The existence of two copies in differing formats, each bearing the inscription “invented by Rembrandt,” initially raises questions about the original composition.

Gary Schwartz, in analyzing the reproduction prints by Vliet and Visscher, notes that “their compositions too are cut off at just the same point […] because both prints were copied after this particular painting.” He further contends that “the model for the prints was not a hypothetical lost original by Rembrandt, but the existing painting here presented” (A Rembrandt Invention: A New Baptism of the Eunuch, 2020, p. 67).

The evident anomalies in J. G. Van Vliet’s print, together with a comparative analysis of the etchings, an intermediate drawing, and a related engraving by Rembrandt, support the conclusive determination that the original composition was conceived in a horizontal format — and that this painting served as its model.

Understanding the composition

Visscher’s reproduction print: similarities, differences and clumsiness.

The format and the interplay of gazes are comparable to those in the painting, and the figures recall those in Van Vliet’s version. The principal difference between this painting and Visscher’s copy lies in the markedly different depiction of the baptismal act, with Philip raising his left index finger in the print. This gesture, in which Philip appears to administer the baptism himself, may evoke The Baptism of the Eunuch by Abraham Bloemaert (1620–1625).

Visscher arranged his scenario to achieve a meaningful double page version by sacrificing the transitional landscape we find in the painting. However, it produced disproportionate figures, while the present painting demonstrates accurate and harmonious proportions.

Unlike Vliet’s print, and arranged as in the present painting, the figures in the eunuch’s entourage are all focused on protecting the eunuch, looking either at the baptism or at the viewer, except for the commanding horseman gazing into the void.

Vliet’s reproduction print.

As expected, J.G. van Vliet is predominantly faithful to Rembrandt’s models.

Gary Schwartz cites in his book “The essential factor here is the sum total of the motifs, and not the way they are set out in the composition.” J. Bruyn, op. cit. (note 32), p. 53. See also Schuckman, Royalton-Kisch and Hinterding, op. cit. (note 28), p. 45.

“[…] The arguments for regarding the present painting as van Vliet’s model are not to be denied.” Gary Schwartz, A Rembrandt Invention: a new baptism of the eunuch, 2020, p. 69.

A closer examination of Van Vliet’s work reveals anomalies inheritated from the crude change of composition.

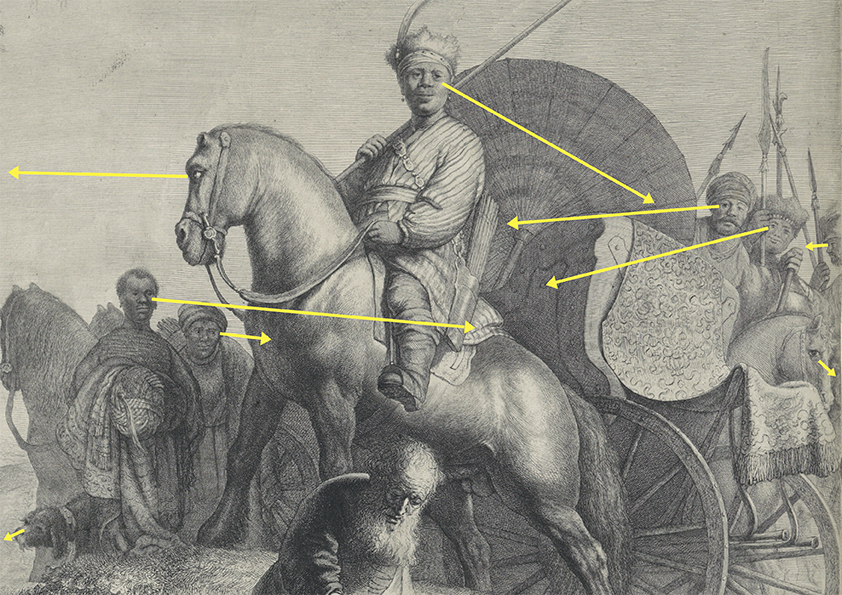

The inconsistency of the gazes of the entourage.

The gazes of the entourage are disconnected from the main scene, which is unusual in Rembrandt’s overall œuvre. They cannot fulfill their duty of protection of the dignitary Ethiopian.

Five of the six figures surrounding the eunuch exhibit a pronounced strabismus.

Looking closely at the faces of the entourage, we notice that Vliet struggled to reorganise the gazes of the characters by reorienting the eyes directions.

None of the characters seems concerned by the sacred act that is taking place before their eyes. Only the animals are in alert but looking toward the foliage rather than the scene.

According to Gary Schwartz in A Rembrandt invention: a new Baptism of the eunuch, 2020, “the auxiliary figures are all looking in the wrong direction. The gazes of the rider and the rest of the entourage make perfect sense in the horizontal painting and perfect nonsense in van Vliet’s vertical print.”

All the painted copies in vertical composition exhibit the same anomalies, sometimes even worse, clearly proving that they are copies of Van Vliet’s engraving and not of the 1630 painting (see below in “copies of Vliet’s engraving after Rembrandt”).

A troublesome iconography detail.

A troubling iconographic detail: the genitals of the horse on Saint Philip’s head.

This anomaly is another strong indication of the unfortunate side effect caused by the abrupt change in format.

The anomalies found in Vliet’s engraving indicate a change in format which required adaptations that Vliet could not resolve on his own.

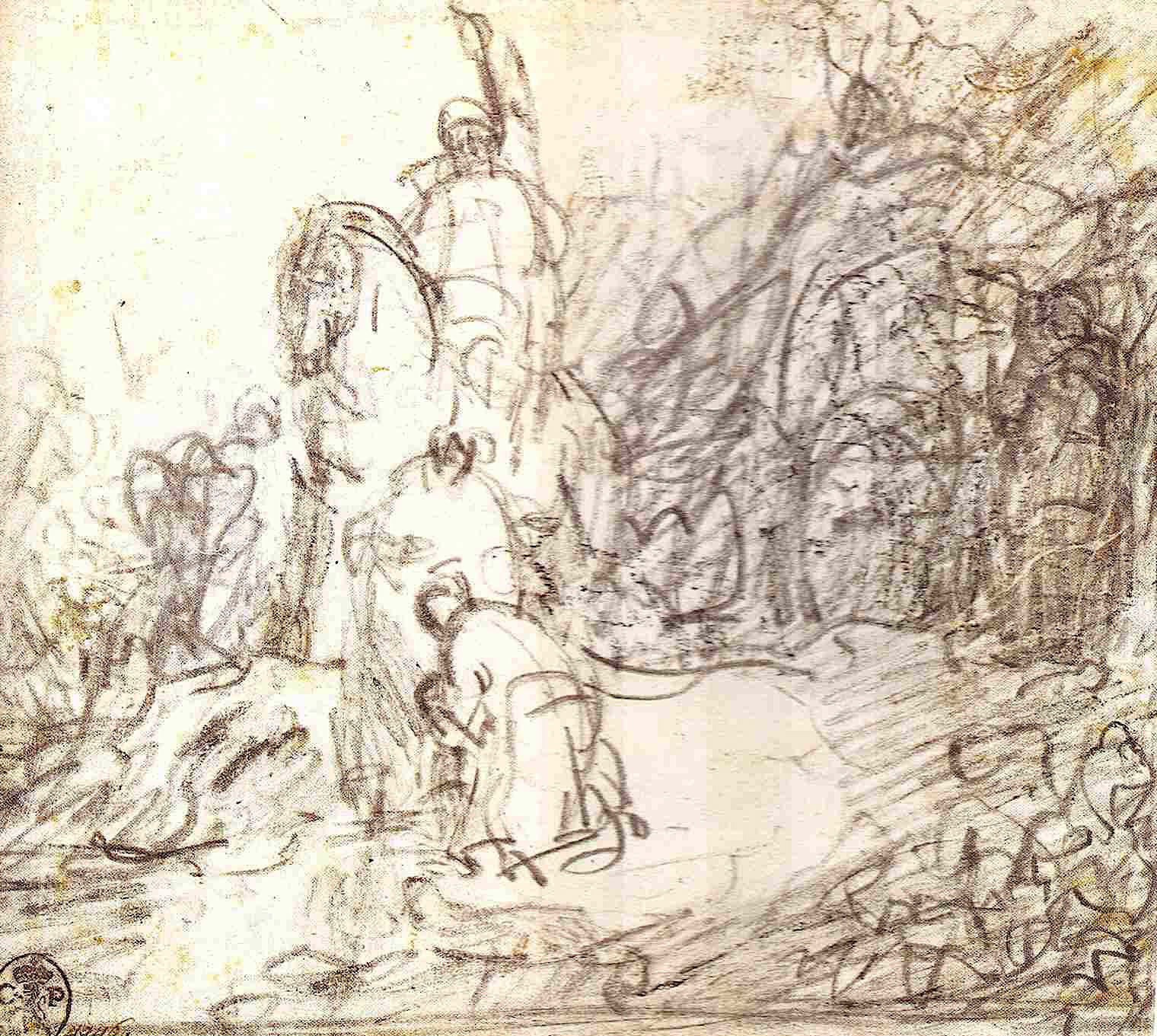

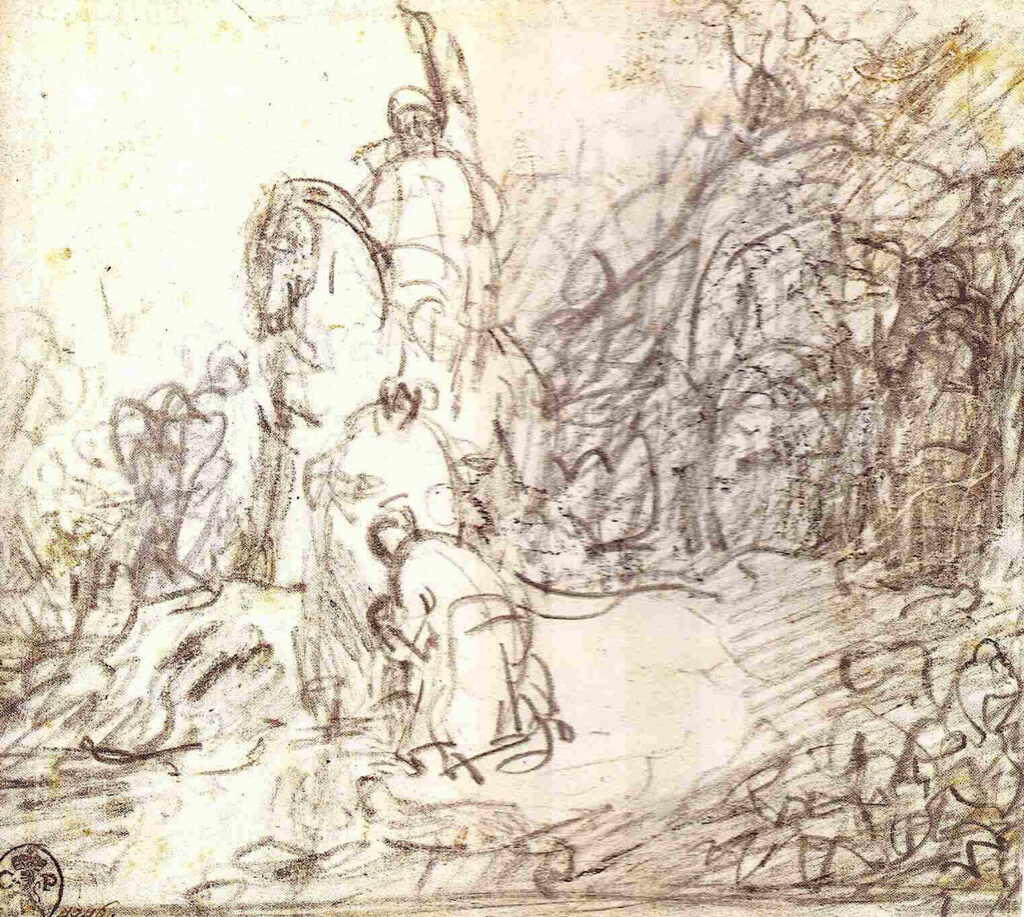

The discovery of a Rembrandt drawing revealed their link and a deliberate change in format.

Rembrandt probably made this drawing to explain to Van Vliet how he could adjust the format.

The faces of the eunuch’s entourage are only roughly sketched. The facial expressions remain indistinct. This absence of head’s expression can explain the anomalies in Van Vliet’s work, as he didn’t have the proper material to align the heads of the figures surrounding the eunuch toward the main scene.

“Rembrandt occasionally made preparatory drawings to [for] changes in a composition”, van de Wetering, E. (1997) Rembrandt: The Painter at Work. Revised edn. Berkeley: University of California Press. Preface, p. xii.

At the time, Rembrandt and Vliet were in Leiden, and Rembrandt likely produced the drawing quickly to guide Vliet in reformatting it. By 1631, however, Rembrandt’s frequent travels between Leiden and Amsterdam likely hindered his supervision, leading to inconsistencies in the engraving. Vliet repositioned the eunuch’s entourage above Philip and the eunuch, replicating their poses but failing to incline their gazes toward the central scene—a departure from Rembrandt’s typical vertical compositions. His clumsy attempt to recenter the gazes resulted in pronounced strabismus and inappropriate juxtaposition of the horse’s genitals with Saint Philip’s head—something Rembrandt would never have done for his own work.

According to Otto Benesch, Wolfgang Wegner, Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Christian Tümpel, Marian Bisanz, Martin Royalton-Kisch, Gary Schwartz, and Odilia Bonebakker, the Munich Baptism of the Eunuch drawing is believed to belong to Rembrandt’s early period and was not created in preparation for the etching by Rembrandt in 1641. The article written by Odilia Bonebakker on Rembrandt’s drawing in Munich (2003) presents concordant arguments “to suggest that the drawing was made around the same time as the lost painting of 1629/30.”

Prof. Dr Odilia Bonebakker, Rembrandt’s drawing of The Baptism of the Eunuch in Munich: Style and Iconography p.39. Rembrandt and his followers, drawings from Munich, Thea Vignau-Wilberg (2003).

From Rembrandt’s original horizontal painting to Vliet’s vertical etching explained by Prof. Dr Fernando Garcia-Garcia:

Gary Schwartz, Volker Manuth, and Fernando García-García (a specialist in drawing) identify Rembrandt’s Munich drawing as a preparatory work based on the present painting, “serving as the model for the vertical composition in Van Vliet’s reproduction print” (Gary Schwartz, A Rembrandt Invention: A New Baptism of the Eunuch, 2020, p. 32).

Rembrandt’s drawing of The Baptism of the Eunuch (Munich) served as a basis for the composition of Van Vliet’s vertical etching, preserving its narrative and stylistic elements.

Iconography: the pictorial tradition

A remarkable continuity: Rembrandt’s 1630 painting in the tradition of baptism of the eunuch representations since the 3rd century AD.

The painting The Baptism of the Eunuch from circa 1630 belongs to an ancient pictorial tradition. This tradition includes manuscripts, frescoes, and reliefs of sarcophagi, which present the essential elements of the theme: Philip, the eunuch, a scroll text, a horse-drawn wagon (sometimes) with one horse facing the viewer, a page and a dog.

Philip and the eunuch sit in a chariot drawn by four horses, while on the right, the deacon stands at an altar in a ciborium.

There are identifiable features from which Rembrandt could draw inspiration. For example, Jan van Scorel (1495–1562) stayed in Rome around 1522, where he entered the Dutch pope Adrian VI service. He was appointed curator of the Vatican’s art collections—effectively responsible for antiquities (a kind of proto-curator). This position allowed him to consult the Menologium and study Roman reliefs. Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574) also went to the Vatican.

Fidelity to pictorial tradition and enduring iconography define the master’s approach and elevates his creative power.

Rembrandt’s distinctive vision in reimagining the baptism beyond his predecessors.

According to the baptism of the Ethiopian Eunuch from the New Testament (Acts 8:26-39), the Eunuch receives the light of the Holy Spirit. Rembrandt subtly introduced a focal point (1.5 cm illuminated circle) that distinguishes him from his predecessors’ interpretations.

A discreet and enigmatic miracle, performed by a divine ray of light. This tiny halo appears as a “visual exegesis,” symbolizing God’s presence and embodying the allegorical significance of a spiritual light that purifies the soul without altering the color of the skin.

“Most of all, the painting expresses dignity, the dignity and self-possessedness of all the figures, engaged in a mysterious rite of solemn portent.” Gary Schwartz, A Rembrandt Invention: a new baptism of the eunuch, 2020, p. 75.

Depicting the baptism performed solely under divine light signifies a purposeful departure from both traditional and contemporary interpretations.

Continuity in retelling the same narrative a decade later.

The mirrored composition, key figures, and recurring details are elements of invention that could only have been conceived by Rembrandt.

Rembrandt reproduces his artistic qualities, even graphic imperfections, from his swift and inspired process.

Philip’s hand and arm.

Philip’s arthritic hand is rendered identically.

Ten years later, in 1641, his foreshortening of St. Philip’s arm is still awkward, but Rembrandt softened it with the interruption of the cloak, which allows the arm to appear more naturally integrated with the shoulder. Let’s note that there are other arms forshortenings in Rembrandt’s œuvre such as Jesus in Christ Appearing to Magdalena at the Tomb, 1638.

The best known Rembrandt painting with an inaccurate foreshortening of the arm.

Soft evolution of the Ethiopian Eunuch gesture.

It’s as if the 1641 engraving, executed ten years later was a new sequence, seconds later, with a tilted angle. The hands clasped on the chest and raised to the sky.

Presence of the same ornaments.

In the etching, the page holds the turban with a more ornate aigrette pointing upward.

Ten years after, the lack of attention given to the page’s hand, which could have been wrongly interpreted in the painting, is surprisingly worse.

Just like in the painting, behind the page, the dog with the collar observes and seems ready to bark.

The great significance of replicating minute details of the painting: the tiny characters.

The small figures might not only animate a biblical landscape. They could also represent Saint Philip, the exegete, seated before the angel, instructing him to help the eunuch to interpret the text and to convert him. The recurring postures of these figures across both works recall Heemskerk’s scene in his engraving on this theme.

When he sold the painting in 1641, Rembrandt created an etching of the scene, preserving its narrative elements and meticulous details.

Stylistic analysis

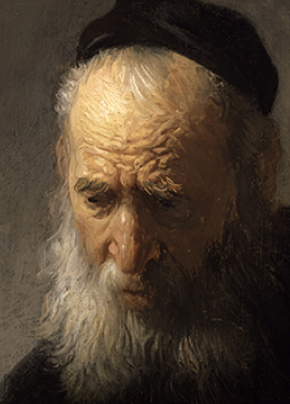

Understanding the ‘rough’ style through the old men in the 1630s and after (e.g., 1633).

According to Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt’s painting style evolved not only across different periods but also within the same period, often exhibiting radical variations. During Rembrandt’s early period, his style was frequently more “rough” as The Head of the Old Man in a Cap, c. 1630, than “fine” as Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem, 1630. Van de Wetering successfully persuaded the Rembrandt Research Project team of this observation. He references J. Bruyn: “We now agree that his conception, backed with impressive argumentation sourced from contemporary texts from Rhetoric, is an argument that makes the range of styles within the same period entirely acceptable.” (What is a Rembrandt? Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt Paintings Revisited: A Complete Survey, Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings VI, p. 52).

St. Philip’s head in The Baptism of the Eunuch (c. 1630) is distinguished by its dynamic application of short, curved brushstrokes in a varied chromatic range. The modulation of browns, ochres, and white highlights—particularly in the scratchy beard and the tousled curls on the forehead—infuses the composition with psychological tension and emotive resonance. The work conveys a nuanced balance of delicacy and force. In terms of style, it bears close affinities to Rembrandt’s production in Leiden, notably drawings and oil sketches such as the Bust of an Old Man (c. 1630), Head of an Old Man in a Cap (c. 1630), and The Bust of an Old Bearded Man (1633) executed in Amsterdam. The painterly treatment of Philip’s head is especially noteworthy on this intimate scale (9 cm x 5 cm), maintaining the vitality and spontaneity of a sketch while conveying the observational acuity of a life study.

Typical of Rembrandt brushwork.

The Morelian detail (a small, often overlooked feature in a painting) of the open mouth showing teeth, as seen in the horseman of the present painting and The Laughing Soldier, c.1630, is characteristic of Rembrandt’s brushwork.

See Ernst van de Wetering, Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings VI, Springer, 2017, p. 42 (fig.49).

Rembrandt often mixed painting and drawing with the brush…* This feature is also present in this painting. *Ernst van de Wetering in Corpus VI, Rembrandt pp. 35-50 and pp.120-145, and in The Painter at Work (1997), pp. 155–190.

The order of working from back to front is typical of Rembrandt’s artwork. Ernst van de Wetering in The Painter at Work Chapter II, pp. 32-36

The reserve around the head of the eunuch in the present painting is a common feature in Rembrandt’s work. Rembrandt strategically uses reserved areas to suggest light, atmosphere, and spatial openness. Through houding, he sharpens details in key passages (like the eunuch’s hair curls) while softening others (such as the unpainted space), guiding the viewer’s gaze and enhancing spatial. Ernst van de Wetering in The painter at Work Chapter II, Painting Materials and Working Methods of the Young Rembrandt, pp. 28, 37, 43.

The Characters in the back and/or in the dark are often found in Rembrandt scenes. They are painted with an incredible economy of means, yet they are particularly expressive.

The texture of the chestnut horse’s coat is not rendered in flat areas, but rather through fine, slightly diagonal parallel strokes. This approach suggests the direction of the hair and adds relief to the painted surface. This technique imparts a more lifelike and natural appearance to the coat, avoiding flatness and enhancing the dynamic quality of the fur. These lines are applied with subtle variations in orientation, according to the animal’s form and the play of light across its body.

Despite being an early work, the painting already demonstrates Rembrandt’s distinctive brush techniques, some of which would later become his signature strokes.

Rembrandt’s pictorial technique implied a thorough knowledge of the materials and the result of the various mixtures used. Over the course of his career, Rembrandt employed a wide variety of materials, creating his own unique superimpositions and exploiting transparencies and materials, which he sculpted for more “realistic” effects. In the painting, the gold chains of the eunuch and the main horseman, the embroidery and the latter’s quiver are noteworthy. This advanced work enables him to achieve maximum effect with minimum means.

A unique light treatment.

The baptism by light: The light of the Holy Spirit pours down in its fullness from Heaven, illuminating Philip’s hand and spilling from there onto the hair of the Eunuch.

Other scenes where Rembrandt favored this light treatment, streaming down from the right include: David Presenting the Head of Goliath to Saul (1627), The Supper at Emmaus (1629), Belshazzar’s feast 1635-1638, among others.

Physical properties: the painting is in good and stable condition

The three boards of baltic wood that make up the panel have undergone the effects of time.

The panel has been trimmed on all borders at different points in time, however the senestre side’s crude cut is notable. The back of the panel has been thinned to prevent worm damage.

Retouchings by restorers

and original execution

Minor variations in texture observed in certain areas, which may affect the perception of Rembrandt’s hand; these are the result of successive restoration campaigns, particularly along the panel joints.

Condition report

In his report (July 22, 2022, Paris) on the present painting, M. van de Laar (former Rijksmuseum painting conservator) states “The condition of this painting is stable and very good.” Following the advice of Michiel Franken from the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD), the restoration was carried out by Regina Costa Pinto (former restorer at the Louvre) under the supervision of Ger Luijten and Fernando García-Garcia.

Michel van de Laar notes: “the damages, fillings and abrasion along and around the original two gluing joints and the two prominent cracks are concurrent for a 17th century painting with this construction. Study of the painting under UV reflection light, with the LED torch, a loupe and with the naked eye shows that the retouches of the last restoration were carried out skillfully, carefully and with the finest precision.”

The imperfections along specific panel joint lines are unmistakable evidence of the restorers’ interventions and cannot be attributed to hypothetical workshop involvement.

Scientific research

These analyses confirm the painting’s authenticity, with materials and techniques consistent with Rembrandt’s known works from the period. Further examination reveals no significant alterations or overpainting, supporting its original integrity.

Dendrochronological analysis by Prof. Dr Peter Klein confirms that the painting’s three panels are made of Baltic oak, with a terminus post quem for use as a painting support around 1630–1631. This coincides precisely with Rembrandt’s preparatory drawing of c.1630 for the engraving by J. G. van Vliet, in which both the invention and the date 1631 are clearly inscribed.

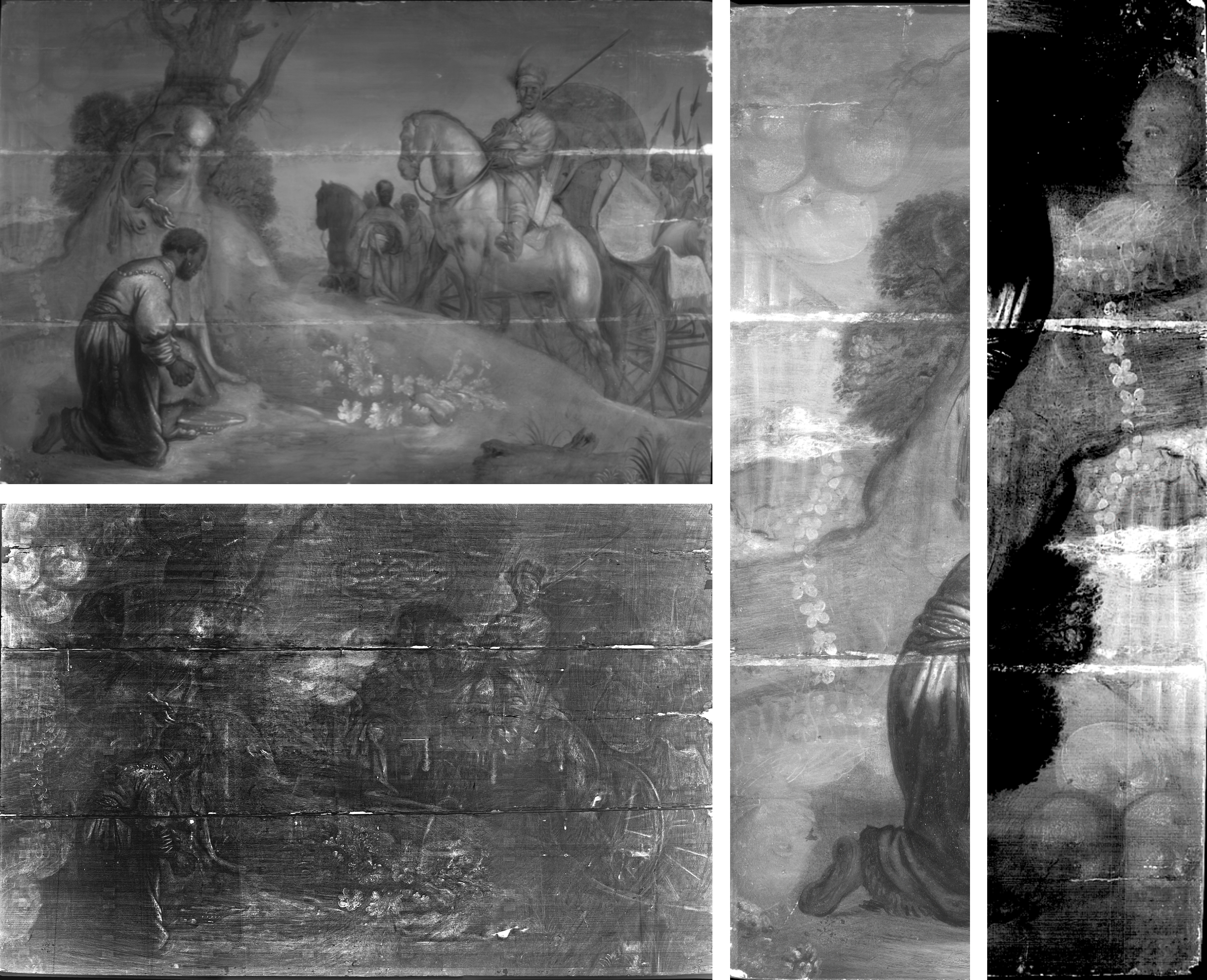

The Reflectography & X-ray, UV fluorescence photography, and Infrared reflectography were directed by Art in Lab on the 27. 10. 2022. They show an older image, upside down, which was typical of Rembrandt’s practice.* Ernst van de Wetering wrote: “The X-radiograph shows the kind of freely executed traces of an earlier image, which could indicate double use of the panel, so typical of Rembrandt.”* Rembrandt made some thirty paintings on top of other paintings.

*A corpus of Rembrandt paintings, vol. VI, Rembrandt’s paintings revisited: A complete survey, (Notes to the plates), Dordrecht (Springer) 2017, p. 503, nr. 45, Oil study of an old man, c.1630, Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst.

Understanding the pentimenti

“The term “pentimento” should be kept for the changes made to a painting that has already been partly or fully worked up.”

Ernst van de Wetering, The Painter at Work, Chapter II, Painting, Materials and Working Methods of the Young Rembrandt: p.42, (figs. 42,43,44).

Multispectral and reflectography analysis conducted by Lumière Technologie also showed the remaining portions of foliage that Rembrandt subsequently covered over perhaps to rebalance the composition and erase foliage that had been rendered superfluous due to the cut on the right side.

inverted low angle false colors, and negative value multispectral

views showing the covering of the Eunuch’s garment at his right knee level.

We may also notice the covering of a portion of the Eunuch’s garment in front of the knee, which is still visible in Vliet and Visscher’s prints.

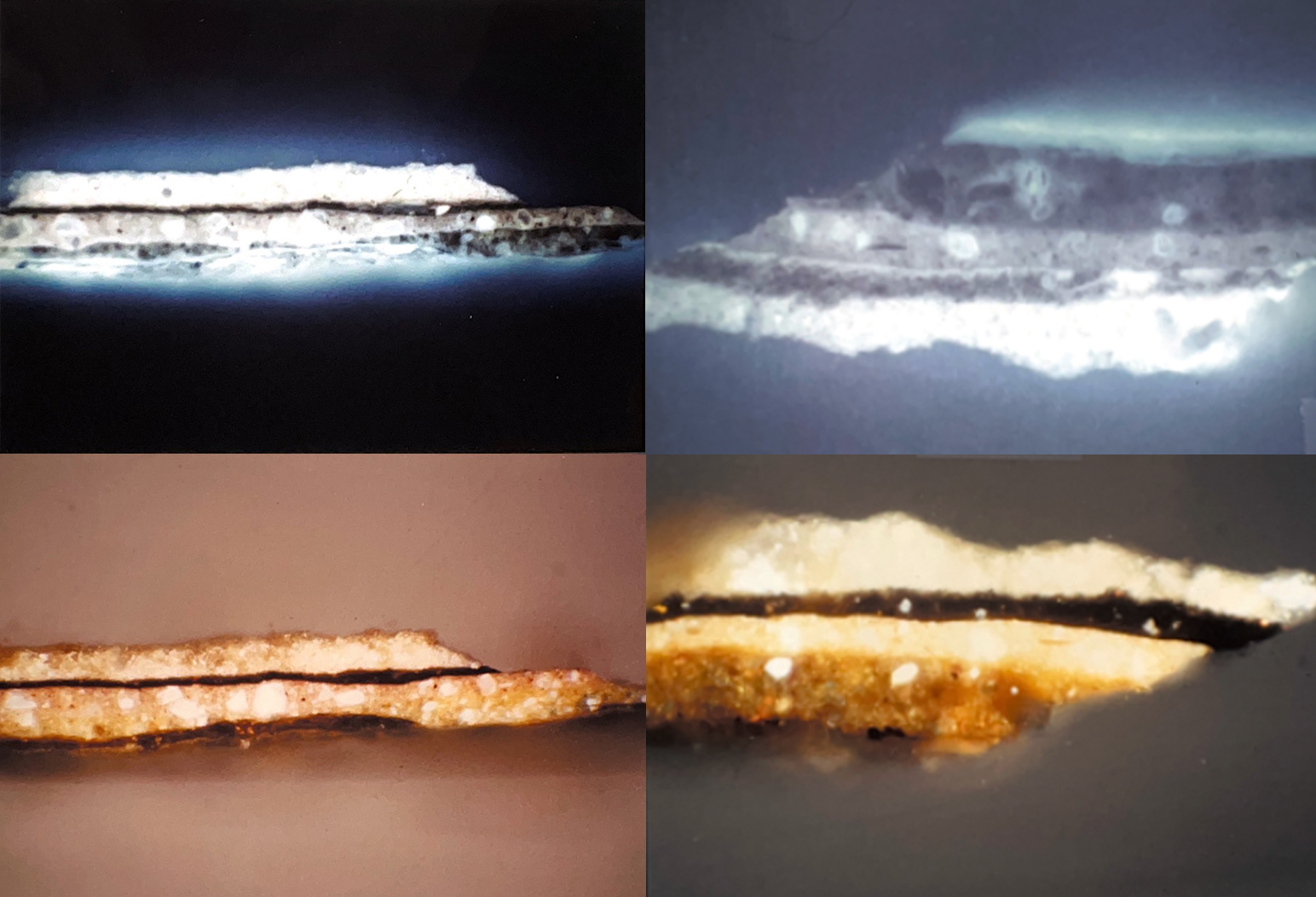

Dr. Hermann Kühn studied the pigments (from extracted fragments) and stratigraphy by stereo binoculars, microscope, macro photography, and UV in Mme Brans’ workshop, Paris, on February 5th, 1985.

The oak panel of Rembrandt’s The Baptism of the Eunuch (ca. 1630–31) is prepared with a whitish-yellow ground composed of lead white and calcium carbonate (chalk), bound in linseed oil. This is followed by a black imprimatura or primuversel containing finely ground lamp black, red iron oxide (ochre), and traces of lead white bound in linseed oil. A thin, UV-fluorescent surface layer indicates the presence of a mastic-based glaze or varnish.

This analysis corresponds to Rembrandt’s late Leiden-period technique. It is closely related to Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver (1629), where the same pigment selection and application method are used. This is documented by Van de Wetering, Rembrandt: The Painter at Work (2000), pp. 97–155, 209–211, Hermann Kühn: Rembrandt’s Painting Materials. (1986), pp.187–201 and Raymond White & Jo Kirby: In Art in the Making: Rembrandt (1988), pp. 104–110.

All scientific analyses provide compelling evidence for a Rembrandt autograph work.

Provenance and traceability

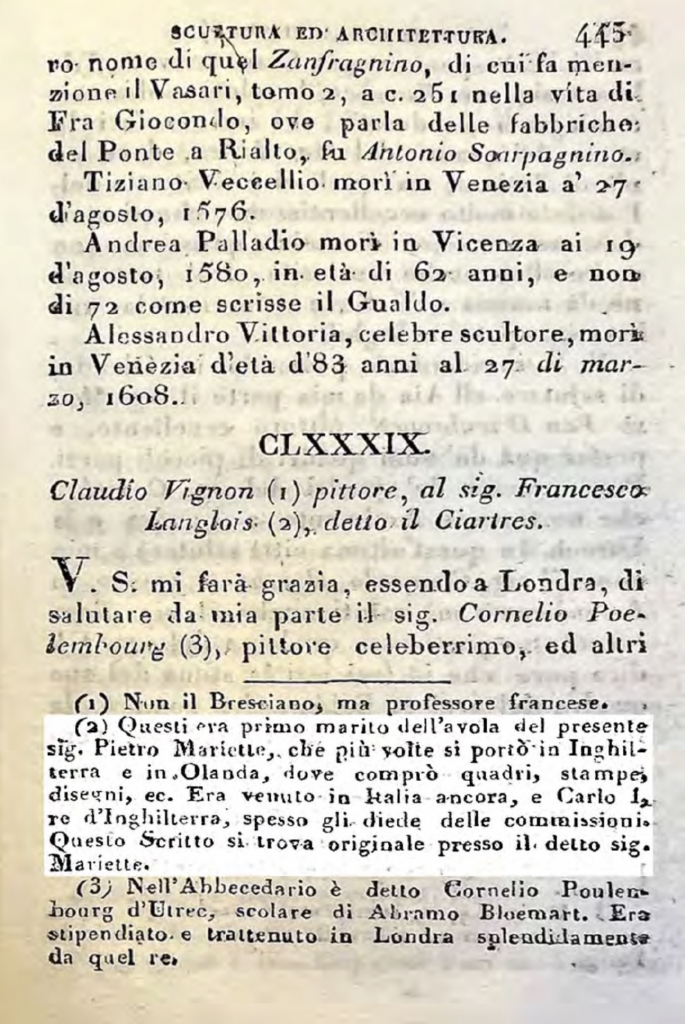

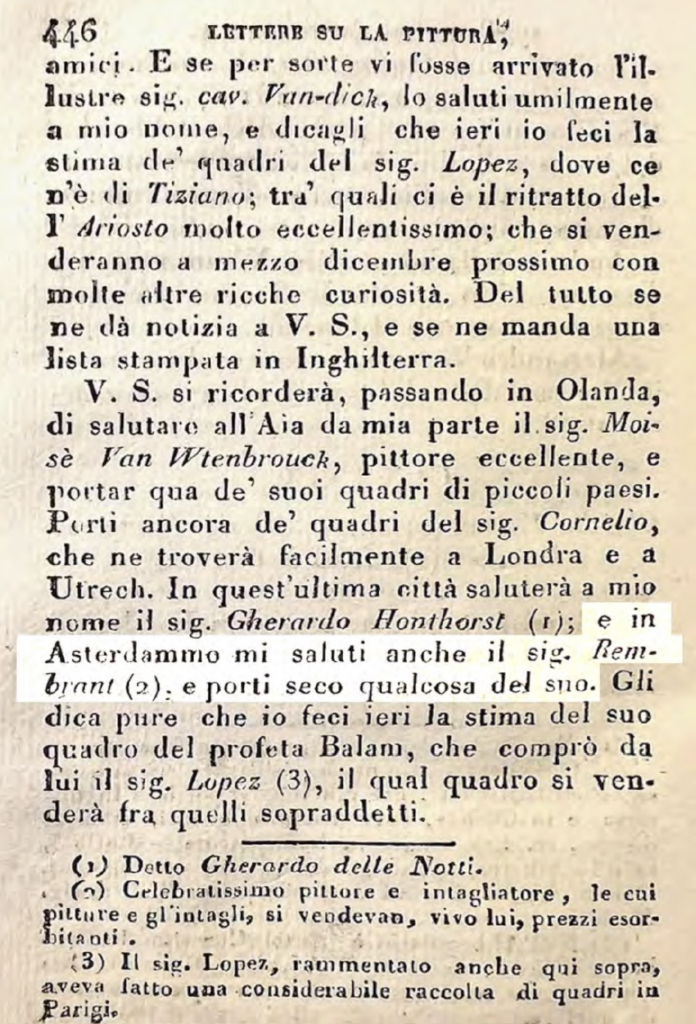

The earliest likely record of the painting’s direct purchase from Rembrandt dates to 1641, when François Langlois—acting on behalf of his friend Claude Vignon (see letter)—acquired the work directly from Rembrandt. Vignon later produced a painted copy a large detail of the original.

Documented presence of the painting in France circa 1641.

Around November 1641, Claude Vignon, French painter, member of the Académie Royale, probably acquired the painting from the art dealer François Langlois after his visit to Rembrandt.

Page 445 of the “Lettere su la pittura, scultura ed architettura”

There is a faithful painted copy probably made by Vignon himself around 1641, which attests to its presence in France during this period.

The striking resemblance between the fragment painted by Vignon and Rembrandt’s Baptism of the Eunuch (ca. 1630), as noted by Claude Vignon specialist Dr. Paola Pacht Bassani, establishes several points:

It confirms a direct connection with Rembrandt’s work, which Vignon’s close friend F. Langlois.

Reportedly brought back from Amsterdam, as detailed in Vignon’s mission letter. Langlois was well aware of Vignon’s deep interest in this theme, as Vignon had painted it in 1638 for the “Mays” of Notre Dame. June 27, 1638, Vignon named his son Philippe and Langlois became his godfather, underscoring the theme’s personal significance. This likely influenced Langlois’s decision to choose this work specifically for Vignon.

Vignon tended to produce his own copies of certain paintings he acquired before reselling them. His reproductions in such cases were often executed with speed, focusing on the central fragment—Philip baptizing the eunuch.

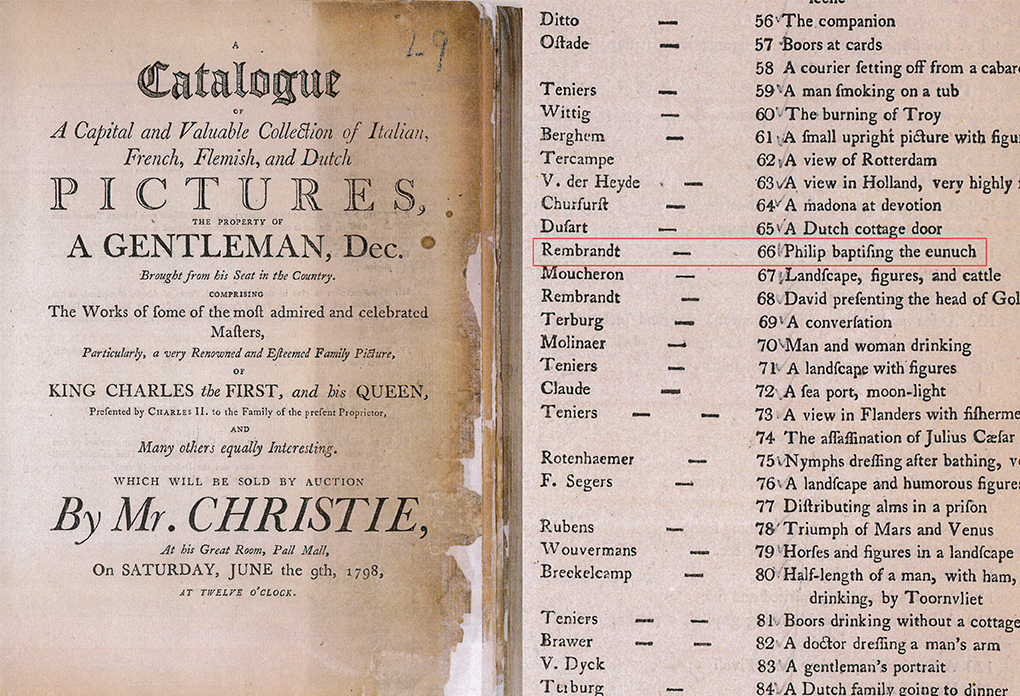

Paola Pacht Bassani, ‘Claude Vignon’ (1593-1670), Arthena, 1993, ‘Vignon et compagnie’ p.65, mentions F. Langlois’ travel to the Netherlands with a visit to Rembrandt (Vignon’s letter of mission to Langlois, November 1641). It’s interesting to note that Langlois was also selling paintings, drawings, and engravings to the Charles I collection, because after the king’s death and the dispersal of the collection, the painting is presented (and sold) in Amsterdam, on April 6. 1695, as Catalogus Schilderyen mentions (lot 48), then sold again in London with the works of the masters of King Charles the First collection (reconstituted by Charles II), on June 9. 1798, as Christie’s catalogue mentions (lot 66).

A testimonial painting: evidence supporting Claude Vignon’s acquisition and direct copy of Rembrandt’s Baptism of the Eunuch, ca. 1630.

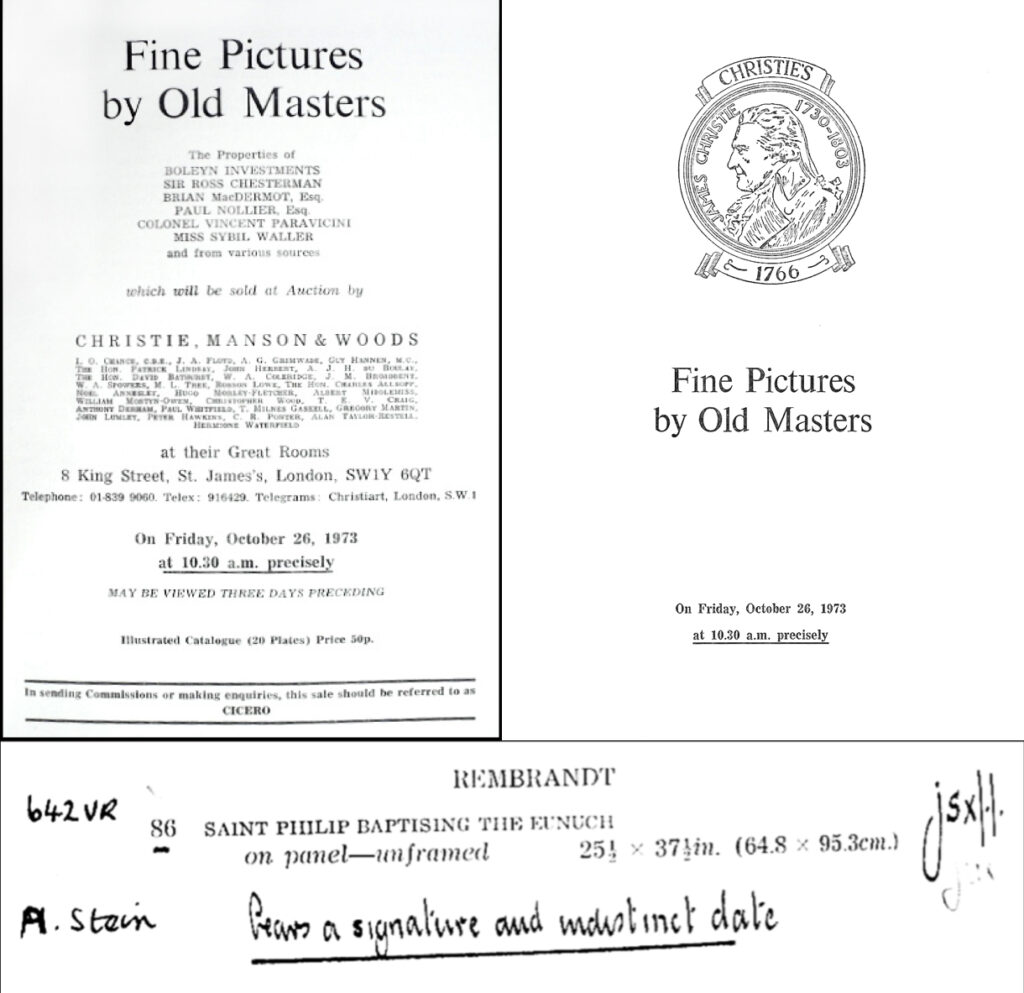

The Baptism of the Eunuch in London in 1798 and again in 1973.

Christie’s sales catalogue with auctioneers’ handwriting showing the exact dimensions of the painting with the same lot 86 and Christie’s code 642VR printed on the former cradle of the present painting (it is now in a small transparent pocket inserted in the current frame) and the seller’s name: Adolf Stein.

The supposedly lost painting has, in fact, been sold under its rightful attribution on at least three occasions.

Copies of the Baptism of the Eunuch, Rembrandt ca.1630.

Rembrandt’s workshop copies of the painting.

Two of the painted copies of the original artwork (found in the RKD archives) show the painting before it was cut off, in its original proportions.

The workshop copies show the stylistic nuances that differentiate the master from his students.

Two of the painted copies of Van Vliet’s engraving after Rembrandt.

It is interesting to note that all the reproductions after Rembrandt, deriving from Vliet’s print exhibit the same iconographical errors, or worse, probably attemting to solve the eyes directions inconsistency made by the engraver during the change of composition from the horizontal modello (the present painting) by Rembrandt.

These copies of Vliet’s engraving after Rembrandt’s painting suffer from the same lacunae found in the original copy of the engraver.

Taken together, the various arguments, diverse in nature, form a mutually reinforcing and coherent web, all converging on the conclusion that this is a highly compelling work by Rembrandt.

The painting already exhibited

2019 Leiden: Museum of Lakenhal

2020 Basel: Kunstmuseum

Virtual tour– Room 6

2021 Potsdam: Museum Barberini

Virtual tour – Look for Room 1A3 and click on the painting to zoom in the artwork

Even before the latest decisive findings for its attribution to Rembrandt van Rijn, the painting was already included in several exhibitions.

Literature

- 1986, Hermann Kühn: “Rembrandt’s Painting Materials.” In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, vol. 1, pp.187–201, edited by Robert L. Feller, Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986.

- 1988, Raymond White and Jo Kirby. In Art in the Making: Rembrandt (A survey of Rembrandt’s paint techniques and materials), edited by David Bomford, pp. 104–110. London: National Gallery Publications, 1988.

- 2017-2019: Ernst van de Wetering, regarding the attribution of the painting, circa 1630, to Rembrandt, recommended referring to his writings as follows:

- 2000, Ernst Van de Wetering concerning stratigraphy: The Painter at Work. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000, pp. 97–155, 209–211.

- 2005, Ernst van de Wetering, Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. IV: The Self-Portraits. Dordrecht: Springer, 2005. p. 628: The Head of an Old Man in a Cap, c.1630 (A. Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University), identified as the model for St. Philip’s head.

- 2008, Ernst van de Wetering, A Life in 180 Paintings, Missing Paintings, Local World BV, 2008, p. 46.

- 2009, Ernst van de Wetering, The Painter at Work, Chapter II, Painting Materials and Working Methods of the Young Rembrandt, University of California Press, 2009, about the order of working, reserve, pentimenti. pp. 28, 32, 36-37, 43.

- 2015, Ernst van de Wetering, A corpus of Rembrandt paintings, vol. VI, Rembrandt’s paintings revisited: A complete survey, (Notes to the plates), Dordrecht (Springer) 2015, p. 503, nr. 45, Oil study of an old man (c.1630), Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst) and p. 509, nr. 56.

- 2017, Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt Paintings Revisited: A Complete Survey, Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings VI, Springer, 2017: about the style: Laughing soldier (c.1630) p. 44, fig. 49 and the old men: Bust of an Old Man (c.1630), p. 42, fig. 47 and p. 97, no. 36, fig. 5, Oil study of an Old Man in a Cap, (c.1630), p.p. 41-42. (Notes to the plates) p. 503, nr. 44, and brunaille, Bust of a Bearded Old Man (1633), p. 172, nr 103.

- 2019, Christiaan Vogelaar, Catalogue: Young Rembrandt-Rising Star, Leiden, The Baptism of The Eunuch [cat 53], written by Christiaan Vogelaar. p. 146.

- 2020, Gary Schwartz publishes A Rembrandt Invention: A New Baptism of the Eunuch (Primavera Press, Leiden), an authoritative and groundbreaking study on the subject. (Elmer Kolfin’s 2021 review, lacking firsthand examination and marked by misquotations and misinterpretations, adds no meaningful value.)

- 2023, Volker Manuth report: The rediscovery of The Baptism of the Eunuch, ca. 1630, by Rembrandt, Summary and conclusion.

- 2023, Gary Schwartz Report: in which, the art historian attributes The Baptism of the Eunuch, ca. 1630 to Rembrandt.

- 2025, An interactive knowledge bank, the Art Model System dedicated to The Baptism of the Eunuch by Rembrandt, ca. 1630 is available upon request.

Acknowledgements

This research benefited from the contributions of many individuals. Gratitude is extended to Ernst van de Wetering, Gary Schwartz, Volker Manuth, Ger Luijten, Christiaan Vogelaar, Odilia Magdalena Bonebakker, Michiel Franken, Fernando García-García, Michel van de Laar, and Regina Costa Pinto for sharing their notes, sources, and expertise, which greatly informed this work. Thanks are also due to the Fondation Custodia, Paris, where The Baptism of the Eunuch was kept, with particular appreciation for Ger Luijten, the former director. Photographies of “The Baptism of the Eunuch” used in this research was provided by Gilles Alonzo and Doro Keman.

Disclaimer

The content provided on this website is for informational and educational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, no guarantee is given regarding its completeness, accuracy, or timeliness. The views and interpretations expressed on this site are those of the authors and do not constitute professional advice. This website is non-commercial and is intended solely to promote knowledge and appreciation of art. It does not offer valuations, certifications, or any other professional services. All materials, including text and images, are shared in good faith and with respect for intellectual property rights. If you are the rightful owner of any material published on this website and believe it has been used without proper authorization or credit, please contact us. We will address your concerns promptly and take appropriate action. By using this website, you acknowledge and agree that the owners and contributors of this site shall not be held liable for any errors, omissions, or any damages arising from its use. Thank you for supporting the appreciation of art!